Views

m (moved 李提摩太 to Timothy Richard 李提摩太: New Protocol) |

m (→Biography: typo) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

Richard was born on October 10, 1845 in Carmarthenshire in the south of Wales. He was baptized in [[1859]], in the midst of the Second Evangelical Awakening in Wales and England. In [[1869]] he was accepted into the Baptist Missionary Society and sailed for China the same year, arriving in Yantai 煙台 where he lived until 1875, when he moved to Qingzhou 青州. | Richard was born on October 10, 1845 in Carmarthenshire in the south of Wales. He was baptized in [[1859]], in the midst of the Second Evangelical Awakening in Wales and England. In [[1869]] he was accepted into the Baptist Missionary Society and sailed for China the same year, arriving in Yantai 煙台 where he lived until 1875, when he moved to Qingzhou 青州. | ||

| - | It was after moving to Qingzhou that Richard began to dress in Chinese clothes and to study Chinese religious texts, including the Confucian classics, the ''Qingxinlu'' | + | It was after moving to Qingzhou that Richard began to dress in Chinese clothes and to study Chinese religious texts, including the Confucian classics, the ''Qingxinlu'' 清心錄 (Records to Clarify the Mind) and the Diamond Sūtra 金剛經 (Jin'gang boruo poluomiduo jing). He also sought local religious leaders to bring his missionary message to "the worthy," following the injunction of Matthew 10:11. Richard saw a common thread of truth running through all religious expressions, a thread he traced back to early Christianity, which he believed was brought to China by Nestorian Christians and which influenced the development of Mahayana Buddhism. |

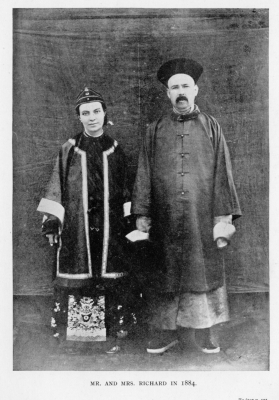

| - | [[File:Timothy_Richard_Chinese_Dress_small.jpg|left|Timothy Richard and wife in Chinese dress]]In his [[1906]] ''Calendar of the Gods in China'', Richard identified vegetarians in China as the "most devout and sincerest people in the land," for<blockquote>in addition to their vegetarianism a large number of them have secretly imbibed much of the mystic teaching of Christianity which the bigoted persecuting Confucianists would not tolerate. The Christian truth brought to China by the Mahayana Buddhism, by Nestorians and by early Catholics is found deeply imbibed in their secret teaching. It only needs the sympathetic spiritual eye to see it under a heathen garb.<ref>Timothy Richard, ''Calendar of the Gods in China'' (Shanghai: Methodist Publishing House, 1906), viii.</ref></blockquote>This was in sharp contrast to most other missionaries and Buddhologists of his day, who saw the older, Theravada tradition as a purer form of Buddhism than the Mahayana tradition followed by Buddhists in most of East Asia. | + | [[File:Timothy_Richard_Chinese_Dress_small.jpg|left|Timothy Richard and wife in Chinese dress]]In his [[1906]] ''Calendar of the Gods in China'', Richard identified vegetarians in China as the "most devout and sincerest people in the land," for |

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>in addition to their vegetarianism a large number of them have secretly imbibed much of the mystic teaching of Christianity which the bigoted persecuting Confucianists would not tolerate. The Christian truth brought to China by the Mahayana Buddhism, by Nestorians and by early Catholics is found deeply imbibed in their secret teaching. It only needs the sympathetic spiritual eye to see it under a heathen garb.<ref>Timothy Richard, ''Calendar of the Gods in China'' (Shanghai: Methodist Publishing House, 1906), viii.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This was in sharp contrast to most other missionaries and Buddhologists of his day, who saw the older, Theravada tradition as a purer form of Buddhism than the Mahayana tradition followed by Buddhists in most of East Asia. | ||

Richard continued to see Mahayana Buddhism as a "higher" expression of religious truth than other religious traditions he saw in China. In his ''Guide to Buddahood'', published in [[1907]], compares "old and new Buddhism" to the Old and New Testaments of the Christian faith, contrasting the "primitive atheistic views" of Hinayana with the "advanced" Mahayana, which has the "God of endless age" Amitābha at its root.<ref>Timothy Richard, ''Guide to Buddhahood: Being a Standard Manual of Chinese Buddhism'' (Shanghai: Christian Literature Society, 1907), i.</ref> | Richard continued to see Mahayana Buddhism as a "higher" expression of religious truth than other religious traditions he saw in China. In his ''Guide to Buddahood'', published in [[1907]], compares "old and new Buddhism" to the Old and New Testaments of the Christian faith, contrasting the "primitive atheistic views" of Hinayana with the "advanced" Mahayana, which has the "God of endless age" Amitābha at its root.<ref>Timothy Richard, ''Guide to Buddhahood: Being a Standard Manual of Chinese Buddhism'' (Shanghai: Christian Literature Society, 1907), i.</ref> | ||

Current revision as of 17:50, 20 September 2013

Timothy Richard (1845-1919)

|

|

Notable Associates:

|

|

Timothy Richard 李提摩太 (1845-1919) was a Welsh missionary who spent 40 years in China, and who studied and published on Buddhism in China.

Contents |

Biography

Richard was born on October 10, 1845 in Carmarthenshire in the south of Wales. He was baptized in 1859, in the midst of the Second Evangelical Awakening in Wales and England. In 1869 he was accepted into the Baptist Missionary Society and sailed for China the same year, arriving in Yantai 煙台 where he lived until 1875, when he moved to Qingzhou 青州.

It was after moving to Qingzhou that Richard began to dress in Chinese clothes and to study Chinese religious texts, including the Confucian classics, the Qingxinlu 清心錄 (Records to Clarify the Mind) and the Diamond Sūtra 金剛經 (Jin'gang boruo poluomiduo jing). He also sought local religious leaders to bring his missionary message to "the worthy," following the injunction of Matthew 10:11. Richard saw a common thread of truth running through all religious expressions, a thread he traced back to early Christianity, which he believed was brought to China by Nestorian Christians and which influenced the development of Mahayana Buddhism.

In his 1906 Calendar of the Gods in China, Richard identified vegetarians in China as the "most devout and sincerest people in the land," forin addition to their vegetarianism a large number of them have secretly imbibed much of the mystic teaching of Christianity which the bigoted persecuting Confucianists would not tolerate. The Christian truth brought to China by the Mahayana Buddhism, by Nestorians and by early Catholics is found deeply imbibed in their secret teaching. It only needs the sympathetic spiritual eye to see it under a heathen garb.[1]

This was in sharp contrast to most other missionaries and Buddhologists of his day, who saw the older, Theravada tradition as a purer form of Buddhism than the Mahayana tradition followed by Buddhists in most of East Asia.

Richard continued to see Mahayana Buddhism as a "higher" expression of religious truth than other religious traditions he saw in China. In his Guide to Buddahood, published in 1907, compares "old and new Buddhism" to the Old and New Testaments of the Christian faith, contrasting the "primitive atheistic views" of Hinayana with the "advanced" Mahayana, which has the "God of endless age" Amitābha at its root.[2]

This idea was further developed in his 1910 book The New Testament of Higher Buddhism, which consists of translations of the Awakening of Mahayana Faith (dasheng qixin lun 大乘起信論), the Essence of the Lotus Sūtra, the Great Physician's Twelve Vows and "The Creed of Half Asia" (the Heart Sūtra). Richard is said to have first become aware of the importance of the Awakening of Mahayana Faith in 1884 after meeting Yáng Wénhuì 楊文會 who was himself converted to Buddhism after reading the book. In 1894 Richard invited Yáng to Shanghai to help with his translation. Anecdotal evidence indicates that Yáng was not pleased with the outcome of the collaboration, complaining that Richard insisted on using his own terms and ended up distorting the meaning of the text.

Richard's significance for the study of Modern Chinese Buddhism lies in his emphasizing of Mahayana texts and beliefs during an age when most European and American scholars of East Asian religion saw contemporary expressions of Buddhism as a syncretic, and thus debased, version of the more ancient and pure Theravada expression.

Important Works

- Looking Backward: 2000-1887 (appeared in serialization 1891-1892)

- This was a Chinese translation of Edward Bellamy's science fiction tale of a future socialist utopia.

- 西鐸 (1895)

- 新政策 (1895)

- New Testament of Higher Buddhism (1910)

Notes

- ↑ Timothy Richard, Calendar of the Gods in China (Shanghai: Methodist Publishing House, 1906), viii.

- ↑ Timothy Richard, Guide to Buddhahood: Being a Standard Manual of Chinese Buddhism (Shanghai: Christian Literature Society, 1907), i.

References

- Richard, Timothy. 西鐸 (The Western Bell). s.n., 1895.

- -----. 新政策 (New Policies), [originally published 1895]. In Hu Bin 胡濱, ed. 戊戌變法 (Shanghai: Xinzhishi chubanshe, 1956), Vol. 3: 232-241.

- -----. "The Crisis in China, and How to Meet it". London: [s.n.], 1897.

- -----. "Some Hints for Rising Statesmen". Shanghai and London: [s.n.], 1905.

- -----. "The China Problem: from a missionary point of view". London: [s.n.], 1905.

- -----. Calendar of the Gods in China. Shanghai: Methodist Publishing House, 1906.

- -----. Guide to Buddhahood: Being a Standard Manual of Chinese Buddhism. Shanghai: Christian Literature Society, 1907.

- -----. "How Each Nation may Possess the Whole Earth". Shanghai: [s.n.], 1907.

- -----. New Testament of Higher Buddhism. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1910.

- -----. “Some Forces in Modern China.” The Contemporary Review (1916). London : A. Strahan: pp. 749-754.

- -----. Forty-five Years in China: Reminiscences. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1916.

- Wikipedia Article on Richard.