Views

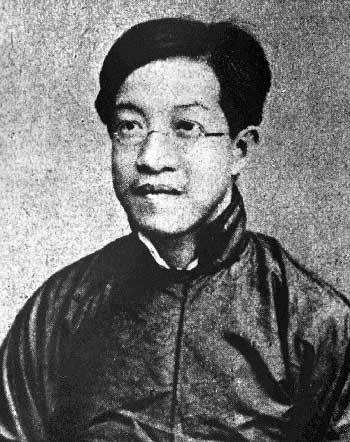

Zhāng Tàiyán 章太炎 (1868-1936)

|

| Notable Associates: |

|

Zhāng Tàiyán 章太炎 (1868-1936) was one of the most important Chinese thinkers of the 20th century. A prominent philologist, scholar, and reformer of the late Qing period, from the first decade of the 20th century he turned increasingly to Buddhism, becoming one of its major scholars in the Republican period.

Contents |

Biography

Zhāng was the scion of a wealthy literati family from Zhèjiāng 浙江 and growing up he received a classical education. At age 23 he completed his studies under one of the most respected scholars in China,[1] Sūzhōu's Yú Yuè 俞樾 (Courtesy name 字: Qǔyuán 曲園, 1821-1907). In his studies and later scholarly work, Zhāng focused on historical phonology and lexicography.

In 1897 (Guāngxù 光緒 23), Zhāng moved to Shànghǎi 上海 and began writings for the Shíwu bào 時務報, during which time he became acquainted with Liáng Qǐchāo 梁啓超 and Tán Sìtóng 譚嗣同. Along with them, Zhāng became involved in the reform movement led by Kāng Yǒuwéi 康有為, but Zhāng's position became more radical than Kāng’s and he eventually called for the overthrow the Manchu government. This shift in his thought was connected to his embrace of social Darwinism, which was associated with criticism of the ethnic minority Manchu government’s control over China’s majority Han ethnicity. At this point in his life, Zhāng also adopted a materialist position, which was based heavily on the thought of the 3rd century B.C.E. Chinese thinker Xúnzi 荀子. He was also highly critical of both the Christian idea of god and Buddhist reincarnation, which he describes as the belief in a transmigrating soul.

After the failure of the One Hundred Days' Reform in 1898, which resulted in the execution of many including Tán Sìtóng, Zhāng fled to Taiwan, then Japan. In Japan he joined forces with Sun Yat-sen, and led a number of revolutionary activities, such as giving pro-reform lectures to the large number of Chinese students living in Japan.

While in Japan began studying Buddhism under Guì Bóhuá 桂伯華.

In 1903 (Guāngxù 光緒 29), Zhāng returned to Shànghǎi. There he continued his revolutionary activities, writing for local papers and publishing revolutionary tracts. On June 13 of that year, after the "Sū bào Incident 蘇報案" he and a number of other pro-reform agitators were arrested and put in jail. While in prison he began to study Buddhism, particularly Consciousness-Only 唯識 thought and Buddhist logic 因明. Although he had studied Buddhism a little bit before this period, this marks his conversion to Buddhism and afterward he became known primarily as a Buddhist scholar. Zhāng eventually rejected materialism (and the evolutionistic ideal of progress) in favor of a worldview based on Consciousness-Only.

After his release from prison in July 1906 (Guāngxù 光緒 32), Zhāng returned to Tōkyō, and joined Sun Yat-sen's Revolutionary Alliance 同盟會. He also attended lectures given in Tōkyō by Yuèxiá 月霞. In attendance were a number of other important figures of the period, including Sū Mànshū 蘇曼殊.

With the founding of the Republic in 1912, Zhāng accepted a post in the government of Sun Yat-sen, but within the year he was put under house arrest at Běijīng's 北京 Lóngquán Temple 龍泉寺 by Yuán Shìkǎi 袁世凱 during the latter's tenure as President/Emperor of China. During this time he bought a copy of the Kalaviṇka Canon 頻伽大藏經, which he had helped Zōngyǎng 宗仰 to publish.

After Yuán's death in 1915, he was released and traveled around with Sun's government.

In general, Zhāng disagreed with the New Culture and May Fourth Movements, and after 1918 he left the world of politics behind to focus on Buddhist scholarship.

He died of illness on June 14, 1936 in Sūzhōu

Important Works

- 章氏叢書

- 章氏叢書續編

- 章氏叢書三編

- 章太炎全集

Notable Students

- Huáng Kǎn 黃侃 (Jìgāng 季剛)

- Qián Xuántóng 錢玄同

Notes

- ↑ Keenan, Barry C. Imperial China’s Last Academies: Social Change in the Lower Yangzi, 1864-1991. Center for China Studies, China Research Monograph, no. 42. Berkeley: University of California, 1994. Pp. 36-37, 50.

References

- Chan, Sin-wai. Buddhism in Late Ch’ing Political Thought. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1985. Pp. 43-46.

- Chang, Hao. Chinese Intellectuals in Crisis: Search for Order and Meaning, 1890-1911. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987. Pp. 104-145.

- Laitinen, Kauko. Chinese Nationalism in the Late Qing Dynasty: Zhang Binglin as an Anti-Manchu Propagandist. London: Curzon, 1990.

- Shì Dōngchū 釋東初. Zhōngguó Fójiào jìndài shǐ 中國佛教近代史 (A History of Early Contemporary Chinese Buddhism), in Dōngchū lǎorén quánjí 東初老人全集 (Complete Collection of Old Man Dongchu), vols. 1-2. Taipei: Dongchu, 1974 Pp. 2.555-559.

- Táng Zhìjūn 湯志鈞. Zhāng Tàiyán zhuàn 章太炎傳 (Biography of Zhāng Tàiyán). Taipei: Taiwan Commercial Press, 1996.

- Yú Língbō 于凌波, ed. Xiàndài Fójiào rénwù cídiǎn 現代佛教人物辭典 (A Dictionary of Modern Buddhist Persons), 2 vols. Taipei: Foguang, 2004. Pp. 1.1112a-1115a.